Researcher Profile: Alexandra Lyon, Former CSFS Postdoctoral Fellow

Dr. Lyon is now Faculty in Sustainable Agriculture & Food Systems at Kwantlen Polytechnic University

How did you get into this field of research?

I see agriculture and the food system as one of the ways that people have a large influence on the environment. I hope that my work has an impact on the environment in a positive way and it helps build towards a more sustainable farming system, contributing to human health.

What is the motivation behind the BC Seed Trials?

People are becoming aware of where their food comes from but farmers often don’t know where their seeds come from, in terms of how they are bred and produced. In my previous research and here in BC, I have found that diversified vegetable growers are concerned about losing access to seeds that are important to them, so they want to find ways to secure their access to those varieties or have more of a say in the way the seed industry works. In the case of organic farmers, since they are a smaller portion of the market, a great deal of the plant breeding conducted and seeds offered in catalogues aren’t focused on their markets and cropping systems. Both organic and conventional farms may have difficulty finding varieties that work in their region, particularly when we are talking about all of the vegetable crops that are grown in BC. For instance, having a tomato that works well in BC is not the same as having a tomato that works well in the Central Valley of California.

The BC Seed Trials identify varieties that will encourage a local seed market. In the Pacific Northwest and BC, we have an ideal climate for growing certain types of seed crops like brassicas (such as kale), spinach and beets, so we are looking first at these seed crops where we have climatic advantage for production. Within those crops, the seed trials will identify varieties that are desired by local farmers. There is a need for farmers to grow seed on a scale where they can really supply what commercial growers need in our area. This activity supports regional seed systems that makes locally selected seed crops available on a larger scale, which allows better access to varieties that work well for this region.

What are the BC Seed Trials?

The BC Seed Trials project involves farmers who grow seed crops in BC and commercial vegetable growers who do not produce seed. We grow a selection of varieties in each crop, from 12 to 30 varieties depending on the crop, and evaluate them based on a range of traits that are important to farmers in BC. Farmers are always concerned with yield, but for direct market growers, appearance and flavour are also very important. Several of our crops also have the potential for season extension, so we look at how well they hold up in storage or in the field in the fall and winter. Our trial sites include the UBC Farm and about 20 participating farms on the Lower Mainland, Vancouver Island, and as far away as Prince George and the Okanagan. This gives us a chance to see the varieties across a wide range of environments and cropping practices, and involve a really great group of farmers in evaluating the varieties and determining what is really needed for a resilient seed system in BC.

Do you find certain varieties do better in different places?

I haven’t finished looking at all of the data yet, but so far we tended to have more consensus among growers about best-performing varieties that I expected given the range of growing conditions. One interesting point of comparison has been between standard commercial varieties and varieties that are from locally grown seeds. In each crop, we have a handful of varieties from independent farmer/plant breeders and public plant breeding programs in BC and the Pacific Northwest that are specifically bred for organic production in this region. We have seen some of these varieties do very well here, and there is a strong potential to continue to improve them.

There is one difference between hybrids and open pollinated varieties. Hybrids are very uniform because every seed is the result of the same cross between two parent lines. But an open pollinated variety has much more genetic variation, and there is potential for the variety to change and become better adapted to a local environment over time. The farmer keeps saving the seed and every time, they always save the best plants. Without even putting much formal thought into it, they are placing a selective pressure on the plant and selecting the plants that grow the best in their environment. That will eventually shift that variety to doing better in that place, and this will happen even faster if done intentionally and using principles of plant breeding. The opportunity to possess varieties that are adapted to the region is part of the importance of having local seed production.

Why are seeds important?

I think of the seed as the package that carries both the genetic material and the science, culture, and history that went into creating that variety. All the qualities that we desire in the varieties that we grow originate in the seed. There are a lot of reasons why the genetic material behind our crops is important, but one is biodiversity. It’s important to have a diverse array of not just the crops that we are growing but also the varieties within those crops. The more agrobiodiversity that we have in our farms and landscapes, the less likely we are to have the problems from monoculture like higher susceptibility to disease. Having a reserve of genetic material behind our crops is an important way to adapt our crops to climate change.

The nature of climate change is such that there is a lot of uncertainty about what sorts of traits will be important in the future. We need to have diverse genetics that are available to farmers and plant breeders for crossing and creating new varieties.

What’s your solution to curbing the loss in biodiversity in agriculture?

One solution is for people to look for different kinds of varieties. Consumers can open up their kitchen and table to a wider array of varieties. This would require accepting something that looks a little different, or being interested in vegetables that are unfamiliar. A positive change is with heirloom tomatoes and apples. This is an example of people going from expecting everyone to have same tomato to having more and more variety. Sometimes, this variety is more expensive so there is an issue around getting the diversity seen in high end restaurants and the gourmet side of the food system into the supermarket on a large scale. Right now, supermarkets want vegetables that are more uniform. Changing the way that we eat and changing the way that the food system is structured so it can handle diverse crops is an important step.

Another solution to losing diversity is supporting local and regional seed systems. Seed systems included seed saving, seed production, plant breeding, and all of the research and infrastructure that get seeds into farmers’ hands. A lot of the work that has been done to preserve agrobiodiversity is supporting farmers to use and grow a greater diversity of seeds, including from local seed systems.

What is your Favourite thing to do at the UBC Farm?

I live near the UBC Farm, so one of the great things is that I can go to the Farm really early in the morning before a lot of people get there; I did that a lot during the summer to check on my trials, and it’s a total escape from the rest of the campus area, walking by the flower fields, watching hummingbird battles – there is so much life in there.

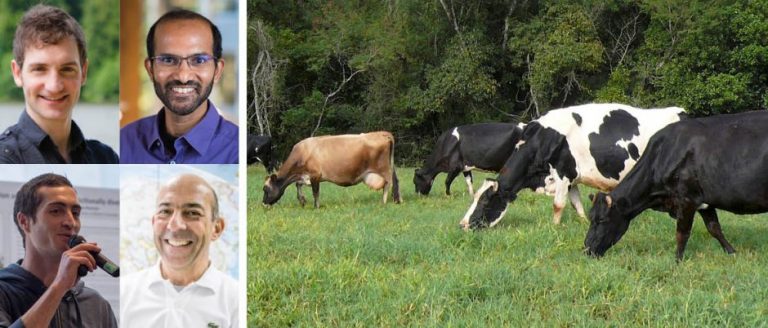

March 2: “Grazed and Confused”: Panel on meat production, climate change, and sustainability

By rachel ma on March 2, 2018

March 2: “Grazed and Confused”: Panel on meat production, climate change, and sustainability

Friday, March 2, 2018, 10:00 a.m. – 11:30 a.m. Room 107 – Aquatic Ecosystems Research Laboratory, 2202 Main Mall

Grazing animals have a significant influence on anthropogenic greenhouse emissions from agriculture. This seminar will invite dialogue on topics related to meat production, grazing, environment and climate Change. For a background document, see the Food and Climate Research Network’s recent report on grazing systems and climate change.

Hosted by: UBC Animal Welfare Program; Centre for Sustainable Food Systems; Institute for Resources, Environment, and Sustainability

Format: three 10-15 minute presentations followed by open discussion.

Panel Schedule:

- Introductions and welcome

- Beyond GhGs: assessing the water footprint of cattle in Southern Amazonia – Michael Lathuillière, IRES PhD Candidate

- Michael Lathuillière is a Ph.D candidate at UBC’s Institute for Resources, Environment and Sustainability (IRES) and has specialized in Water Footprint assessment methods applied to agricultural products. His research focuses on how Water Footprint assessments may guide decision-making in Brazil where soybean and beef production have increased rapidly in recent decades in both Amazon and Cerrado biomes.

- Is reduced consumption of livestock products a strong leverage point to achieving the Sustainable Development Goals? – Navin Ramankutty and Zia Mehrabi

- Navin Ramankutty is Professor and Canada Research Chair in Global Environmental Change and Food Security at the Liu Institute for Global Issues and the Institute for Resources, Environment, and Sustainability at the University of British Columbia. His research program aims to understand how humans use and modify the Earth’s land surface for agriculture and its implications for the global environment.

- Zia Mehrabi is a Postdoctoral Research Fellow at IRES, the Liu institute for Global Studies & the Centre for Sustainable Food Systems. He has worked in industry on large scale farmland expansion in sub-Saharan Africa, in a non-profit setting on developing environmentally conscious decision support tools for land managers, and with small scale farmers on the interactive effects of agricultural intensification and climate change on crop yields.

- Grazing cattle in family farming: welfare for the cow, the farmer and the consumer? – Luiz Carlos Pinheiro Machado

- Luiz Carlos Pinheiro Machado is a visiting professor at UBC Animal Welfare Program. He is as full professor at the Federal University of Santa Catarina, Brazil, where he leads a research group on Animal Agroecology and Animal Welfare, focusing on the behavior and welfare of dairy grazing cows and pasture management. He will present on how the balance (Carbon stocked vs. Carbon release) rather than emissions alone should be considered when evaluating grazing systems. He will relate this to the welfare of animals, quality of life for the farmers and quality of food for the public.

- Open discussion and questions

The UBC Future of Food Global Dialogue Series events are free and open to all. This campus-wide initiative brings together food security and sustainability experts from across the globe to engage the UBC community and the public around the Global Food System.

Preparing UBC graduates for the food systems workplace

By Justin Lee on January 29, 2018

Preparing UBC graduates for the food systems workplace

The Centre for Sustainable Food Systems (CSFS) launched a new wave of LFS Career Development opportunities (LFS 496) in 2016, as a way to increase student access to for-credit, mentored learning experiences with a food business or organization.

“This career development program came as a result of students telling us they wanted to get their hands dirty. They wanted practical experience in the workplace,” says Véronik Campbell, Academic Programs Manager at the CSFS at UBC Farm. Career development placements are posted on the CSFS website, allowing students to apply and interview just as they would for a regular job posting. Students earn 3-6 credits in the course, working directly with a workplace mentor over one or two semesters. Students also form a cohort engaging in professional development activities such as the Strengthfinders assessment, a food values exercise, and a session on improving workplace communication.

“The goal of this program is to prepare our graduates both professionally and academically for future careers in the food system,” says Hannah Wittman, LFS Professor and CSFS Academic Director. “Students actively apply the theory they have received in their undergraduate courses in a conscious, practical way, through on-the-ground food system-related work.”

For some career development placements, students literally get their hands dirty in the fields of the UBC Farm, working with poultry or perennial crops, while other positions focus on food system opportunities such as curriculum creation for children’s food literacy programs or engagement with BC progressive food businesses.

“Participating in a career development placement at UBC Farm showed me how food and sustainability are integral to good health which made me see the UBC Farm as a home of solutions for local challenges that will eventually lead to global changes,” said Sigbrit Søchting, Biodiversity and Perennial Crops student

Career development positions are also growing off campus, where food systems organizations can apply to mentor a student. Previous students have worked with Inner City Farms, the Richmond Food Security Society, and the Working Group on Indigenous Food Sovereignty.

“We also created the program to respond to the needs of BC food systems” adds Ms. Campbell. “We wanted to build resources and empower organizations, and to have this program become an asset for the BC food system, providing highly-qualified UBC graduates that are ready to hit the ground running.”

This article was originally published in the Land and Food System magazine Reach Out, Issue 28 Fall 2017.

How LFS 496 helped prepare Jeffery Kwok for the workplace

By Justin Lee on January 29, 2018

How LFS 496 helped prepare Jeffery Kwok for the workplace

*Disclaimer: The Career Development in Land and Food Systems course is the updated title of the previously-named Career Development in Land and Food Systems Internship.

Jeffrey Kwok, Outreach and Community Engagement Intern, Centre for Sustainable Food Systems at UBC Farm

As part of the LFS Career Development Internship (LFS 496) program, Jeffrey Kwok, a fourth year student in the Applied Animal Biology program, worked with the outreach team at UBC Farm. His role included creating, delivering, and facilitating educational curricula about food system sustainability to school age children and youth. He also worked with stakeholders and community partners exploring the multifunctional role of food and its environmental, social, and cultural implications.How do you think this internship prepares you for the work world?

I think this internship has prepared me for the work world because it has many components that characterize our modern working environment. There is a focus on communication, collaborative work, use of electronic communication as a facilitation tool, dealing with uncertainties, and working with stakeholders with different goals and interests.How would you like to be involved in the food system after you graduate?

I would like to work in promoting food security and food systems sustainability in our local communities. My internship gave me the opportunity to immerse myself into the community of people in Vancouver who work to creating a better food system and I want to be a part of that change.How has the internship influenced your choices or future path?

My internship has fuelled my interest in working in the local food system. It has also opened my eyes to the different career avenues that I can take after I graduate, which elucidated the kinds of jobs that align well with my passion and interests. This article was originally published in the Land and Food System magazine Reach Out, Issue 28 Fall 2017.Hannah Wittman featured in Vancouver Sun article: Vancouver sees increase in farms despite downturn in region

By Justin Lee on January 19, 2018

Hannah Wittman featured in Vancouver Sun article: Vancouver sees increase in farms despite downturn in region

Hannah Wittman, CSFS Academic Director

Our Academic Director Hannah Wittman was featured in the Vancouver Sun: “Vancouver sees increase in farms despite downturn in region”, talking about an increase in farms in Vancouver.

As for the future of urban farms, Wittman doesn’t see a permanent shift toward agricultural use for land in the city. The majority of land area is leased and 38 per cent of farms in Vancouver are on borrowed land, and the use of that land can change as plots are developed or used differently by their owners. “In a sense, urban agriculture is a great interim use of the land, but it doesn’t presume any permanent contribution to food security,” said Wittman. The hope is that urban farms increase food literacy, particularly where food comes from and how it is grown. “What we hope is that it generates greater concern for the decline in farming in very urban areas. When people see how hard it is, how little food is produced, they will start to pay attention to the loss of farms in Richmond or in Delta, where land is being taken out of production due to speculation,” she said.

LFS 496 Student Profile: Meryn Corkery

By Justin Lee on December 14, 2017

LFS 496 Student Profile: Meryn Corkery

*Disclaimer: The Career Development in Land and Food Systems course is the updated title of the previously-named Career Development in Land and Food Systems Internship.

LFS 496 Student Profile:

Communications Intern and Academic Assistant Work LearnSupervisors:

Melanie Kuxdorf (LFS 496) and Veronik Campbell (Work Learn)What are you studying?

I am in my third year in the Global Resource Systems program in LFS.What was your role as the Communications Intern?

As the Communications Intern, my role was to help promote the various programs at the Centre for Sustainable Food Systems through both physical advertising and online methods. Additionally, I also contributed to two major projects: the CSFS Annual Report and a Student-Driven Engagement Strategy.What did you get out of doing this internship?

I think some of the most important takeaways I received from this internship was a supportive work environment and the opportunities to explore different avenues of communication within food systems. Both the Academic Assistant and Communications roles had similar tasks, however, the way I had to approach each one was slightly different. I had to put myself in the shoes of the target audience and think “What would a student need to hear?”, “Where would a professor look for resources?” “How would a community member interpret this statement?”. This made me reconsider the role of media in our lives and how it can bring about systemic change.What was the most surprising thing you learned?

I think one of the most surprising things I learnt was the history of the UBC Farm. I had always known that the Farm was originally a student-run initiative, but I hadn’t realized that it was literally students dragging their professors to the Farm and leading the revitalization of the Farm when it was threatened for development. It was interesting to learn about the dynamic position the Farm is in – straddling both the student and the institutional side, as it offers food for the UBC Campus community but also serves as a living laboratory for students. There are no other University farms like it in North America; most are either entire student-run, small-scale operations, or larger research-only farms.Why are you interested in working within the food system?

Food is uniquely situated at the intersection of many issues that are gaining traction as priorities that need to be addressed. The food system impacts our emotional and physical well-being in varying ways – from the provision of culturally relevant food to being able to meet our nutritional needs, to providing us with comfort and a sense of place. It additionally impacts the physical environment and is a key contributor to climate change. My passion lies where all those intersect – what resultant profession this may lead to is unsure. Food transcends barriers in order to unite us, lending itself as a valuable touch point for change-making. I don’t know the answers to the sustainability problems of the world or how to solve world hunger or decrease inequality, but I do believe that looking at what, how, why and with whom we eat is a good start.What would you like students to know about the CSFS at UBC Farm?

I would like them to know that the Farm is their space – whether they choose to utilize it through an academic, professional, or recreational capacity is up to them. You don’t have to be enrolled in a course to come to the Farm and hang out with the chickens, or volunteer to eat (I mean pick…) blueberries. There are so many physical and psychological benefits of getting outside and engaging with the land again. The Farm is an amazing reprieve from the stressful and fast-paced university life.What is your favourite thing to do at the UBC Farm?

I love walking through the Farm at dusk, as the sun sets over the fields of brassicas. I love going to Farmade and running into many many familiar faces. I love hearing about all of the different research projects going on at the Farm. I love browsing the market and giving my mom a tour when she visits. I love walking into the Farm Centre and instantly feeling welcomed. I love digging my hands in the dirt of a soil pit for my soil science class. So I guess my favourite thing at the Farm is the diverse activities that you can do there and the community you find within in it once you start hanging around enough!UBC Farm Markets featured on Fairchild TV

By Justin Lee on December 6, 2017

UBC Farm Markets featured on Fairchild TV

Check out the Fairchild TV feature on the UBC Farm Markets.

Researcher Profile: Gabriel Maltais-Landry, Former Postdoctoral Researcher

By Justin Lee on December 1, 2017

Researcher Profile: Gabriel Maltais-Landry, Former CSFS Postdoctoral Researcher

Now Assistant Professor, Sustainable Nutrient Management Systems, University of Florida

What drew you to UBC Farm and the CSFS?

I’m process oriented and I like to understand the mechanisms of why things work the way they do. That’s often easier to do on a research farm than on a grower’s field because there is more control over what’s going on. Ultimately, you want to validate your findings on real farms, but I find that the first step of research projects is often easier to complete on a research farm.

What is an organic amendment and how is it different from a fertilizer?

Organic amendments usually refer to compost and manure. They contain large concentrations of organic matter (primarily carbon) and low and variable concentrations of the nutrients necessary for optimal plant growth. In contrast, a fertilizer has a rich nutrient content, low content of organic matter, and it can be organic or synthetic, though most people assume that a fertilizer is synthetic. Synthetic fertilizers contain higher concentrations of nitrogen, for example, urea – a common synthetic nitrogen fertilizer – is composed of 46 per cent nitrogen while poultry manure – one of the organic amendments richest in nutrients – is only about 4 to 6 per cent nitrogen.

What was the overall objective of your research at the UBC farm?

My work at the UBC Farm focused on nitrogen and phosphorus and the interactions between them. I wanted to see how organic amendments and cover crops affected nitrogen and phosphorus cycling, using three different experiments.

Part I: Benefits of rainfall protection during manure storage

What was your first experiment?

The first experiment we set up dealt exclusively with manures and investigated how nutrient content and greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions were affected by rainfall protection during storage. We focused on chicken, turkey, and horse manures, the latter two being under-studied manures. We measured the change in the nutrient content of nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium as well as GHG emissions.

What’s the difference between phosphorus and nitrogen and why are they important?

Phosphorus and nitrogen are the two most limiting nutrients in agriculture. The biggest difference between nitrogen and phosphorus is that we can extract nitrogen from the atmosphere since it makes up 78 per cent of the air we breathe. Nitrogen levels are naturally low in most soils, but legumes have a symbiosis with microbes that allows the plant to fix nitrogen into the soil, making nitrogen available to the plant and other organisms. However, because nitrogen is very mobile in soils, it is often found in concentrations that are too low to support the high yields produced in modern agriculture. In contrast, phosphorus can’t be replenished from the atmosphere since there is no phosphorus in the atmosphere. Phosphorus is naturally occurring in the soil at higher concentrations than nitrogen, but it is slowly depleted over time by erosion and leaching losses, and eventually, it becomes limiting to plant growth.

What is the motivation behind this experiment?

Along with the BC Ministry of Agriculture, we wanted to find out: Do different manures behave differently when they are protected or unprotected from rainfall? How bad is it to leave your manures stored uncovered? We know that in general manures should not be left uncovered because of leaching into soils that concentrate nutrients in a localized area; it’s not an efficient way to manage nutrients. Nutrient leaching also increases risks of pollution to nearby water bodies, where excess nutrients contribute to environmental degradation. We wanted to test the degree to which this depletion occurred. What we found is that different manures don’t behave the same way and that the type of bedding material seems to affect the extent of nutrient loss. Short term storage (less than three months) without rainfall protection was not too bad and had some limited benefits, but long-term storage was definitely not good for any manure type.

Part II: Potential benefits of horse manure in immobilizing nitrogen and preventing leaching

The second project compared the effects horse and chicken manure have on nitrogen availability if applied in the fall prior to the rainy season.

The idea behind testing these two manures is that they have a radically different carbon-to-nitrogen ratio. When there is a high carbon-to-nitrogen ratio, microbes do not release nitrogen into the soil and instead remove it from the soil to access carbon in the manure, a process called immobilization. In doing so, the microbes compete with the plants for soil nitrogen, which can limit plant growth. This would be bad if you are trying to grow a crop, but if there is residual soil nitrogen remaining after harvest, such as from crop residues and fertilizers remaining in the soil, this nitrogen immobilization may be a tool to prevent nitrogen losses from the soil. Nitrogen loss prevention can be enhanced by growing a cover crop, which would take up nitrogen from the soil and reduce the amount of rainfall that leaches through the soil.

Horse manure might immobilize nitrogen since it has a high carbon-to-nitrogen ratio. In contrast, chicken manure shouldn’t immobilize nitrogen because it is high in nitrogen and has a low carbon-to-nitrogen ratio. We applied these two manures in the fall and planted a cover crop for the winter. We looked at how these manures affected soil nitrogen, GHG emissions and spaghetti squash yields. The chicken manure had greater soil fertility and squash yield, but it also had the greatest detrimental environmental impacts. Indeed, soils amended with chicken manure had higher soil nitrogen in the fall and nitrogen leaching risks, GHG emissions, and phosphorus over-fertilization. Overall there was a trade-off between increasing yields and reducing pollution.

Part III: Comparison of different certified organic vegetable production systems

The ultimate goal of the third project was to figure out how to achieve high yields and minimize environmental impacts in different organic systems. To do this we tested four systems that relied on different sources of nutrients: compost, manure, or blood meal (a processed organic fertilizer very rich in nitrogen). We wanted to see how these systems performed, using metrics that incorporate environmental costs such as kilos of yield produced per gram of GHG emissions emitted, per gram of excess phosphorus applied, or per gram of nitrogen applied in the fall that is prone to leaching.

Which treatments worked the best?

As usual in science, there is no black or white answer; it depends on the system and the type of crop. We grew cauliflower, cabbage, beets and fennel. Since cauliflower requires a great deal of nitrogen, it didn’t perform well in the low compost system that minimizes environmental costs: there was 40 per cent to 60 per cent less yield compared to systems that were better fertilized. This would never work for a farmer, and there would be environmental implications too as we would need more land to produce the same amount of food. The beets grown in a low compost system, however, produced 80 per cent of the yields compared to well-fertilized systems. This could be more workable for a farmer, especially if there are incentives to encourage environmental protection. We also compared the yields to the amount of GHG emissions, and the emissions were lowest with the systems using compost as opposed to manure or blood meal.

Why does this research matter?

Agriculture is one of the most important activities on earth in terms of its impact on natural ecosystems. Nutrient management is a huge leverage point to improve the sustainability of our society. Changing the way we manage these systems could maintain the productivity while minimizing the negative impacts. Also, because organic systems have been historically less studied than conventional ones, there is a need to better understand the environmental impacts of different organic management approaches.

What is a key point that you think people should know?

Some people think there is a silver bullet approach, where we’ll find one solution that will fix everything; but in almost every study there is something that will work in a specific context and may not work in another, or it will work for some variable but not for the other. We want to reduce the complexity as much as we can but we also need to embrace it. I don’t think we can produce food without polluting at all. That means we have to be careful with the food we have and reduce the environmental footprint of current food production as much as possible.

What’s your favourite thing to do at the Farm?

Sometimes I would have to go in on the weekends to fix things and being there when no one else is around is really amazing. Vancouver is such a busy place, it feels very relaxing to be in that peaceful environment. I really like the feel of the place. It’s a really great spot; an idealized farm. I’ll miss the eagles!

Dawn Morrison on CBC Ideas

By Justin Lee on November 24, 2017

Dawn Morrison on CBC Ideas

Dawn Morrison, Founder, Chair and Coordinator of the B.C. Food Systems Working Group on Indigenous Food Sovereignty, was featured on CBC Ideas on Indigenous food sovereignty in a radio documentary called: Confronting the ‘perfect storm’: How to feed the future

Researcher Profile: Craig Borowiak, Former Visiting Researcher

By Justin Lee on November 22, 2017

Researcher Profile: Craig Borowiak, Former Visiting Researcher

Associate Professor, Haverford College in Philadelphia

What is the focus of your research?

I am an associate professor and chair of the political science department at Haverford College in Philadelphia. I study alternative political economies and for the past eight years have been focusing my studies on what is known as the ‘solidarity economy’. This refers to economic practices that depart from mainstream capitalist forms by prioritizing collectivist values such as cooperation, democratic decision-making, mutual aid, and community development. My research has a transnational dimension but takes place primarily in Philadelphia.

On a national level (in the U.S.), we have generated a series of maps of the solidarity economy. We’ve been collecting data on social initiatives such as worker cooperatives, credit unions, and community gardens. The mapping platform we have created to facilitate this dataset can be found at www.solidarityeconomy.us. These maps are designed to help the public locate such initiatives. We are also using them to study how demographic factors, such as race and class, relate to solidarity economy initiatives.

Why does this work interest you?

A recurring theme in my work is that communities today face multiple crises, whether they are financial, environmental, or security-related. Frequently, capitalist structures can be found behind these crises. I have a strong belief that in order to create a more vibrant and sustainable society we must find alternatives to the harmful structures of capitalism. But the thought of taking on capitalism is really overwhelming for a lot of people. It is really dis-empowering to think that in order to have alternative options, you’d have to overcome the entire system. At the same time, my work has shown me that maybe our economy is not so capitalist after all. When you begin to notice the cooperative efforts of our society such as public schools, public parks, community gardens, and bike shares, you realize that half of the challenge of coming up with alternatives is learning to recognize them. Once we collectively begin to acknowledge the alternatives that already exist, it becomes possible to leverage them to bring about more systemic change.

When I first taught my students about the idea of reading the economy differently so as to identify non-capitalist practices, many felt that a burden was lifted off of their shoulders. They began to see that there is value in micro-interventions. They began to see such interventions as part of something bigger.

What is your link to sustainable food?

For a long time, my work focused on transnational politics. Once I became more self-conscious about my lack of knowledge in relation to my own city of Philadelphia, I redirected my work away from the transnational angle and towards my local community. I began to immerse myself in local cooperatives, which then led me to the community garden movement. I found this movement fascinating and began speaking with community partners who were struggling to find and maintain data on gardens. I became very involved with this data, discovering that only a fraction of the 1,200 supposed community gardens in the city actually existed. Many of these were merely abandoned, vacant lots. On the other hand, many actual gardens weren’t recorded at all. The detective work of looking into these entries became a major research project. We have now produced comprehensive datasets of community gardens in the city, including data on land ownership and neighborhood demographics. These datasets are currently being used by community partners and the city to help preserve gardens at risk due to gentrification.

When you started your research, did you expect to become so involved in community gardens?

I was surprised that I became so involved. My original goal was to paint a picture of Philadelphia’s solidarity economy, which required a completed list of community garden entries. Upon my involvement, I realized that these gardens are a way of alleviating the existing racialized poverty that is concentrated in Philadelphia. These gardens are a means for underdeveloped communities to beautify their neighbourhoods, enhance their food security, and drive out harmful, illicit activity.

What have you gained from visiting the Centre for Sustainable Food Systems (CSFS)?

One of my primary motivations for visiting the CSFS was that I wanted to be around people who understand these community-based food systems better than I did and who could help me understand how to assess the impact of community gardens. Being in this supportive environment has been incredibly helpful, as I’m surrounded by people who are interested in these questions that I have surrounding community gardens. I’ve also gained perspective about my own city – Philadelphia is a racially segregated city, whereas Vancouver is very different. In Vancouver, there are a completely different set of issues and questions surrounding community gardens. Vancouver struggles with finding space for new community gardens, whereas Philadelphia has trouble planting existing lots.

Where do you see this research heading?

When I set out on this research project, I had wanted to create an estimate of the economic value that we might attribute to community gardens’ produce. Such quantitative metrics are important for policymakers. I have come to appreciate that much of the impact of community gardens is not reflected in the shadow economic value. It’s instead about the human connection, the cultural preservation, the reconnection with nature – qualitative stuff. So what can we do to make these somewhat abstract things legitimate in the eyes of the people in power? Part of the challenge with thinking about alternative food systems is confronting dominant discourses and modes of representation. It’s not that things like community gardens are wholly invisible, it’s that their full value is not legible to policymakers, academics, and the public because of the way we think about the economy and society. Addressing this is the next step of this work.