Ethnobotany

Case study campus food asset:

Plants on UBC Campus

Case study location

UBC Vancouver Campus (follow google map tour), publicly accessible all hours of the day.

Potential case study topics:

Fine Arts, Landscape Architecture, Media Studies, Political Science, Forest Policy, Medicine, Kinesiology, Biology

How to Use this Case Study

- 1. Read the introduction section.

- 2. Read through one or more of the themes below.

- 3. Take the Ethnobotany Plant Tour of the UBC Campus. Use your smartphone (with Wi-Fi) to take the tour. Many of the stops on the tour feature Campus Botanica signage and embedded in each stop on the Google Map tour is a link to the Indigenous Research Partnerships plant database.

- 4. After completing the plant tour of campus, return to the theme(s) and answer the questions.

The University of British Columbia aims to advance knowledge through research, teaching, and community engagement. Innovations and emerging areas of excellence are constantly explored to move forward, towards the unknown.

Yet, sometimes innovation and inspiration can be found in everyday objects that are all around us and hidden in plain sight.

Ethnobotany is the study of the relationship between plants and people. The word ethnobotany is the combination of the Greek root ethno, meaning ‘people’ or ‘cultural group’ and botany, meaning ‘plants’. The field involves a spectrum of inquiry, from the archaeological investigation of ancient civilizations to modern bioengineering. It relies on a multidisciplinary approach involving anthropology, archaeology, botany, ecology, economics, medicine, religion, amongst others.

There are thousands of trees, shrubs, and understory plants native to British Columbia that have historical and contemporary uses by Indigenous people in every aspect of life. The introduction of non-native species—through human-driven disturbance and distribution—has had significant ecological, economic, and social impact.

This case study aims to explore respectful ways to learn about and engage with traditional knowledge about plants found on the UBC campus, and the historical and contemporary relationships that occur between plants and people. Several on-campus initiatives help keep our relationships to plants alive including Campus Botanica, an interpretive plant sign project that engages passersby with culturally diverse ways of seeing and relating to plants; as well as the Indigenous Research Partnerships ethnobotanical plant database.

The geographic centre of this case study is the UBC Vancouver Campus, its landscaping, ornamental gardens, acres of lawn, and endowment. These should be centre-of-mind when engaging with the materials below.

Lastly, consider this quote from Alice Walker, the first African-American woman to win a Pulitzer prize:

“I think it pisses God off if you walk by the color purple in a field somewhere and don't notice it.”

Perhaps the same can be said for not noticing plants in general. Consider this case study and tour as a form of rapprochement.

Gardens can be intrinsically appealing and beneficial to humans. They are sometimes designed to reflect the spiritual and physical use of the space by its current or past community members. They can also follow ethnobotanical attributes:

- adhere to a clearly defined mission;

- and, provide an environment conducive to learning and adapt through time (Jones and Hoversten 2004)

Depending on the history, the geography or culture of a place, a ‘successful’ ethnobotanical garden may greatly vary in its design. Jones and Hoversten (2004) offer the following questions for ethnobotanical considerations in landscape architecture:

- 1. What people/culture is being interpreted?

- 2. What was their relationship to this place/this site/this area?

- 3. What processes and outcomes are interpreted?

Landscape design on the UBC Campus acknowledges the traditional relationship between plants and people on this land. In courtyards and sidewalk plant beds, many plants with ethnobotanical purposes have been incorporated in the landscape. The UBC Botanical Garden curates a collection of 50,000 plants, many of which found in key ecosystems such as the British Columbia rainforest and Garry Oak meadows. The UBC Farm boasts several hedgerows reflecting a biological diversity that includes endemic plants with cultural significance.

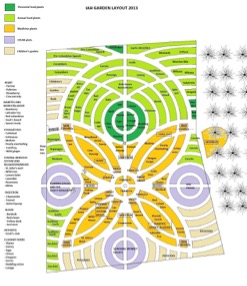

The xʷc̓ic̓əsəm Indigenous Health Research & Education Garden at the UBC Farm represents a key example of how ethnobotany can be at the centre of the design process for healing or health gardens. In 2013, students, community members, and elders worked together to design the garden in a way that would reflect and honour local Indigenous and ecological principles. The shape and physical design of the garden now incorporates a Musqueam spindle whorl at the centre of the space. The inclusion of traditional native plants used for medicinal, food, fibre and dying purposes was guided by the insights and deep knowledge of the Medicine Collective, a group of Indigenous elders and knowledge keepers. In 2016, the garden was gifted the name xʷc̓ic̓əsəm by xʷməθkʷəy̓əm (Musqueam) Elder Larry Grant, which means "place of growing" in the hən̓q̓əmin̓əm̓ language.

Attribution: IAH_Garden_Planting_Plan_June_7_2013 by Alexander Suvajac under CC BY 2.0

Examples of Health Areas and Plants used for Medicine

Diabetes: Bearberry, Labrador tea, Red Columbine, Goat’s Beard

Heart: Yarrow, Valerian, strawberry, cow parsnip

Digestion: Chamomile, Fennel, Anise hyssop

Questions:

- 1. Why are plants hidden in plain sight? What are the implications of losing awareness of the presence and diverse uses of plants in our everyday lives?

- 2. How are plants with ethnobotanical purposes suited to the campus landscape? Do they seem out of place?

- 3. Evaluate the interpretive signage you visited on the Ethnobotanical tour. Did the information help you gain a deeper understanding? Why or why not?

- 4. What kind of signage or resources creates a more meaningful learning experience?

Reading:

Suvajac, A. 2013. Institute of Aboriginal Health Garden: Design Process Summary Text.

Suvajac, A. 2013. Institute of Aboriginal Health Garden: Design Process Summary Visual.

These documents summarize the design process for the xʷc̓ic̓əsəm Indigenous Health Research & Education Garden at the UBC Farm. It provides details of the goals and considerations for the space, which were deeply informed by the knowledge from elders and community members.

The discipline of ethnobotany has emerged as an important interlocutor in federal and provincial policy decision around Indigenous Peoples’ land rights and titles in Canada. In June 2014, the Supreme Court of Canada granted the Tsilhqot’in Nation the full Aboriginal title for the grounds their people inhabited exclusively at the time when representatives of the British Crown staked claims 250 years ago (2014 SCC 44). How did the Tsilhqot’in prove the extent of their land rights? Partly through ethnobotanical investigation. During the trial, distinguished ethnobotanist Nancy Turner offered her opinion that the Tsilhqot’in people have been present in the Claim Area for at least 250 years based on the length of time required to develop the names and knowledge of the Claim Area plants used for food and medicine (2014 SCC 44).

The study of how ethnobotany can be applied to policy development, planning, and decision-making is at the forefront of Dr. Nancy Turner’s emerging research. Demonstrating people’s dependence on plants for their well-being and their absolute need for ecosystem integrity in their territories can be a compelling approach to contest intrusions from the Crown (Turner 2015). Research around traditional management of plants and landscapes is now, more than ever, a priority to ensure that Indigenous people in British Columbia are recognized as cultivators of the land and they can maintain or gain the right to their land under the Canadian government land claim criteria.

Questions:

- 1. What role do young people play in the future of ethnobotany? Are they equipped to incorporate traditional plant uses into decision-making?

- 2. How can we raise the profile of traditional plant uses to achieve a higher and more influential profile to inform provincial and federal policy? What role could the university play in achieving this?

- 3. What are key components in the code of ethics before research is undertaken relating to cultural knowledge and practices in ethnobotany?

- 4. What are the barriers to referencing ethnobotanical uses in the court of law?

- 5. How might other challenges involving environmentally damaging activities in the face of climate change benefit from the study of ethnobotany?

Reading:

Turner, N., and Lepofsky, D. 2013. Conclusions: The Future of Ethnobotany in British Columbia. BC Studies 179 (Autumn 2013): 189-209.

The authors consider the modern state of ethnobotany in British Columbia, which strives to integrate Western and non-Western knowledge in effective and respectful ways. Case studies explore plants role in education, the importance of Indigenous foods, and learning opportunities for plants in healthy diets.

Video: Nancy Turner - Indigenous Environmental Knowledge & Environmental Values in Land Use Planning.

Introduction to Nancy Turner’s Indigenous environmental knowledge & environmental values in land use planning project.

Ray, A. J. 2015. Traditional Knowledge and Social Science on Trial: Battles over Evidence in Indigenous Rights Litigation in Canada and Australia. The International Indigenous Policy Journal, 6(2).

This article explores how traditional knowledge and oral history poses numerous challenges in Aboriginal claims litigation including how and where this information can be presented, who is qualified to present it, questions about whether this evidence can stand on its own, in Canada and Australia.

Ethnobotanical and ethno-medicinal knowledge has been preserved through the ages in written or oral form. While some of this traditional knowledge (e.g., for herbal medicine) has been incorporated into Western medicine (Fakim 2006) and research of plant resources in traditional medicine has intensified with the aim of finding new cures for different health conditions (Wachtel-Galor and Benzie 2011), chemically synthesized drugs, in many parts of the world, have been prioritized as the main way to revolutionize health care.

Throughout history, Indigenous peoples were coerced into abandoning their cultural beliefs and practices in relation to health care through the process of colonization. Their loss of control over the land base and its resources contributed to the systematic destruction of Indigenous knowledge and cultural systems (Obomsawin 2007). Only recently has the scientific establishment recognized that traditional healers were highly gifted persons, subject to years of exhaustive training, and whose understanding of nature and the workings of the human body-mind complex surpassed that of western science (Obomsawin 2007).

Today, the challenge lies in sharing traditional medicinal knowledge across cultures. Posey and Dutfield (1996) argue that the ethnobotanical literature (journal articles, databases, and field collections in particular) serves as a major source of information and ideas for researchers and industries with commercial objectives. End users of this information are often third parties who have had no direct contact with the Indigenous communities whose knowledge they are appropriating (Barnett and Banister 2000). To counterbalance this tendency, medical professional and Indigenous healers need to create a space for dialogue and knowledge sharing. At UBC, the Indigenous Research Partnerships aims to further develop research and education on areas of shared priorities between the Indigenous community and the university. The support of knowledge synthesis, translation and exchange from an Indigenous lens can help to stimulate innovating research in the field of medicine.

Questions:

- 1. Which of the plants on the tour have contributed to western pharmaceutical products? How?

- 2. What are the costs and benefits of allowing knowledge of plants and their functional biomedical components to fall under intellectual property rights?

- 3. What alternative models or examples exist that acknowledge and properly attribute traditional knowledge in the development of new medicinal products?

Reading:

Ellison, C. 2014. Indigenous Knowledge and Knowledge Synthesis, Translation and Exchange (KTSE). Prince George, BC: National Collaborating Centre for Aboriginal Health.

This discussion paper examines the theory and practice of knowledge synthesis, translation and exchange (KSTE) within public health in Canada. The author acknowledges that Indigenous knowledge can work with existing methods and theories of knowledge translation, but also requires its own KSTE process.

Barnett and Banister (2000). Challenging the status quo in ethnobotany: a new paradigm for publication may protect cultural knowledge and traditional resource. Cultural Survival Quarterly Magazine.

Fakim (2006). Medicinal plants: Traditions of yesterday and drugs of tomorrow. Molecular Aspects of Medicine, 27(1). 1-93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mam.2005.07.008

Jones and Hoversten (2004) Attributes of a Successful Ethnobotanical Garden.. Landscape Journal, 23(2): 153-169.

Obomsawin (2007). Traditional medicine for Canada’s first peoples.

Tsilhqot’in Nation v. British Columbia,. SCC 44. (2014).

Turner (2015). Trudeau project: Making a Place for Indigenous Environmental Knowledge and Environmental Values in Land Use Planning and Decision-making.. The Pierre Elliott Trudeau Foundation. Montreal, QC.

Wachtel-Galor and Benzie (2011).Herbal Medicine: An Introduction to Its History, Usage, Regulation, Current Trends, and Research Needs. In I.F.F. Benzie, S. & Wachtel-Galor (Eds), Herbal Medicine: Biomolecular and Clinical Aspects. 2nd edition. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press/Taylor & Francis.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.