Indigenous Food Sovereignty

Places to visit on campus: UBC Vancouver campus is located on the unceded, traditional and ancestral territory of the Musqueam people.

- The Reconciliation Pole, Main Mall, between Agronomy Road and Thunderbird Boulevard on UBC’s Vancouver Campus is publically accessible all hours of the day.

- At the UBC Farm, visit the Tu’wusht Garden Project, xʷc̓ic̓əsəm, the Indigenous Health Research and Education Garden, and the Maya in Exile Garden.

- The Indian Residential School History and Dialogue Centre on Main Mall will open in April 2018.

Case study topics: History, Information Science, Anthropology, Food, Nutrition and Health, Political Science, Law, Economics, Geography, International Relations, Human Relations.

Acknowledgements: This case study was developed with the input and insight of Brianne Lee, Dawn Morrison, & Hannah Wittman.

Attribution: Photo by UBC is licensed under CC BY 2.0.

- 1. Read the introduction section.

- 2. Read the chapters Indigenous Land and Food (Morrison and Wittman, 2017) and Indigenous Food Sovereignty: A Model for Social Learning (Morrison, 2011) and additional readings suggested below.

- 3. Listen to the CBC Ideas interview with Dawn Morrison, Founder, Chair and Coordinator of the Working Group on Indigenous Food Sovereignty: The hidden power of food: Finding value in what we eat.

- 4. Read through one or more of the Themes.

- 5. Visit one of the case study sites at UBC (Reconciliation Pole, Dialogue Centre or UBC Farm.)

- 6. Return to the themes, read the material, and answer the questions.

At the University of British Columbia, we are encouraged to question our assumptions, beliefs, and values; to think deeply about the important issues of the day; and to develop habits of mind that will allow the next generation of thinkers to address humanity's most troubling causes.

But when are we asked to question the assumptions, beliefs and values of UBC itself?

This case study is one of those opportunities. Here, we examine issues related to indigenous food sovereignty– including the colonialization and transformation of traditional regional food systems, land rights and access, and pathways to decolonizing research and relationships. We aim to learn to identify and understand the tensions, contradictions, and challenging ways forward towards better understanding Indigenous people’s food systems, and how they interface with other expressions of food systems in mainstream culture. The geographic centre of this case study is the Reconciliation Pole; however, it is the campus itself, the land upon which UBC is situated (e.g. its buildings, parking lots, walkways, ornamental gardens, acres of lawn, and endowment), that should be centre-of-mind when engaging with the materials below. Further, it is important to keep in mind that components of this case study have significant overlap and similarity with Indigenous struggles with colonialization of their traditional lands and territories, and beyond.

The UBC Vancouver campus is located on the traditional territory of the Musqueam community. In 2006, UBC and Musqueam formalized relations through a Memorandum of Affiliation. This memorandum is the formal base of relationship that UBC seeks to have with the Musqueam and other Indigenous communities, and since then, a number of initiatives have been started.

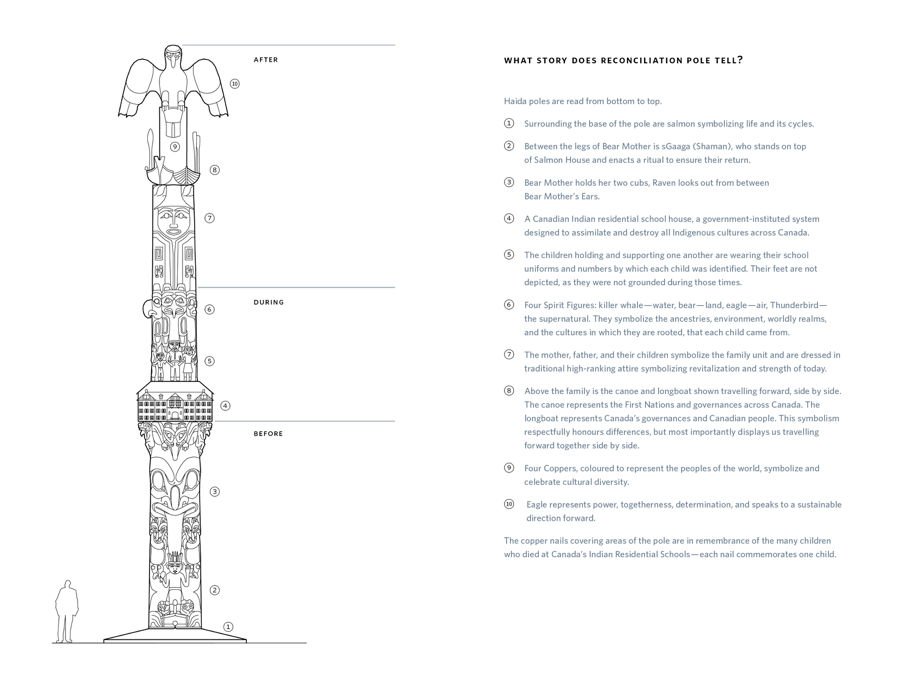

On April 1, 2017, the Reconciliation Pole was installed at the UBC Vancouver campus, on the traditional lands of the Musqueam First Nation. The pole illustrates the long trajectory of Indigenous and Canadian relations to ensure that one part of that, the history of Canada’s Indian residential schools, will never be forgotten (UBC, 2017). The Indian Residential School History and Dialogue Centre will house records and historical material and provide a place to discuss experiences, history, and its effects and implications.

Attribution: Pole-diagram-full-size from UBC under is licensed under CC BY 2.0

In the years leading up to the 150th Anniversary of Canadian Confederation, the Centre for Sustainable Food Systems collaborated with the Working Group on Indigenous Food Sovereignty on Indigenous food sovereignty and social resiliency issues in British Columbia. Dawn Morrison is from the Secwepemc nation and is the founder of the Working Group on Indigenous Food Sovereignty (WGIFS). Dr. Hannah Wittman is the Academic Director of the UBC Centre for Sustainable Food Systems (CSFS).

Dr. Wittman and Ms. Morrison’s discussion in the book chapter, Indigenous Land and Food, explores the potential of addressing the social and environmental injustices of Indigenous peoples by going to the “learning edges” between settler allies and Indigenous peoples and by working together to decolonize research and relationships. While universities can serve as research-intensive institutions contributing to the public interest, academia can also be a tool of colonization, appropriation, and oppression (see Connecting Communities: Principles for Musqueam-UBC Collaboration, 2015). However, by working closely alongside community organizations, universities can also serve as partners to build and foster the social learning that can support a more socially and environmentally just food system for all.

Who are Indigenous people?

According to the Centre for Indigenous Peoples’ Nutrition and Environment, McGill University, ‘Indigenous people’ refers to a cultural group in a particular ecological area that developed a successful subsistence base from the natural resources available. The plural form, 'Indigenous Peoples', refers to more than one cultural group.

Indigenous Food Systems

Indigenous food systems include all of the land, soil, water, and air, as well as culturally important plant, fungi, and animal species that have sustained Indigenous peoples over thousands of years of participating in the natural world (Indigenous Food Systems Network, 2017). Since the time of colonization, Indigenous communities have experienced a drastic decline in the health and integrity of their cultures, ecosystems, social structures and knowledge systems. Complex systems of Indigenous biodiversity and cultural heritage have been endangered in the process of colonization and resource extraction and this has affected the ability of Indigenous communities to achieve adequate amounts of healthy foods (Reading & Wien, 2009). Beyond health, what are the other impacts?

Indigenous Food Sovereignty

Indigenous food sovereignty refers to a reconnection to land-based food and political systems from a disconnected state often driven by colonization (Martens et al, 2016). It moves beyond access to food, and is grounded in the idea that people should be able to self-determine their food systems and cultural traditions. La Vía Campesina, a group of land-based peasants, farmers, and Indigenous peoples, devised the term food sovereignty in the early 1990s to protest the corporate control of global food systems (Wittman, 2011). Dawn Morrison outlines the key principles of Indigenous Food Sovereignty in Canada as Principles for Social Learning.

An Indigenous food is a plant, animal or fungi that has been primarily harvested, cultivated, taken care of, prepared, preserved, shared, or traded within Indigenous cultures and economies. In hunting, fishing, farming and gathering strategies adapted over multi-millennia, Indigenous peoples persist in harvesting a wide diversity of plants and animals used as foods and medicines in the forests, fields and waterways.

Complex systems of Indigenous biodiversity and cultural heritage in the land and food system have made major contributions to society and are being rapidly eroded in the face of modernization and technological development (Barthel et al, 2013). The breakdown of inter-generational transmission of knowledge has resulted from forced assimilation into Indian Residential Schools and public education systems where young people are no longer systematically being taught important Indigenous food-related knowledge, wisdom, or values by their families and communities.

Just as there is great diversity in Canada’s Indigenous communities, there is a great variety of indigenous foods (see, for example, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (1996).

The Centre for Indigenous Peoples’ Nutrition and Environment at McGill University developed a procedural manual for understanding and Documenting Traditional Food Systems of Indigenous Peoples. Nuxalk Nation from coastal BC is one of the groups included in this study. This project gathered traditional food data through key informants and focus groups. This tool could help reconnect Indigenous people to land-based food and political systems and work towards food sovereignty.

Readings:

-

- Morrison, D., 2011. Indigenous Food Sovereignty – A Model for Social Learning. in: Wittman, H., Desmarais, A.A., Wiebe, N. (Eds.), Food Sovereignty in Canada: Creating Just and Sustainable Food Systems. Fernwood Publishing, Halifax, pp. 97–113.

This chapter reviews the development of the principles of Indigenous Food Sovereignty in Canada, recognizing that supporting Indigenous food sovereignty requires a deepened cross-cultural understanding of the ways that Indigenous knowledge, values, wisdom and practices can inform food related action and policy reform. This chapter examines the main principles of Indigenous food sovereignty as well as current issues, concerns and strategies that have been identified in recent discussions, meetings and conferences in Indigenous communities towards building an Indigenous food sovereignty movement in B.C. and beyond.

-

- Turner, N. J., et al., 2009.Chapter 2: The Nuxalk Food and Nutrition Program, coastal British Columbia, Canada: 1981-2006. In: Indigenous Peoples’ food systems: the many dimensions of culture, diversity and environment for nutrition and health.Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

The authors, working with the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, assess how a group of Indigenous Peoples from coastal British Columbia themselves researched their food diversity, cultural understanding of their food and the impacts of the environment on their food. The authors conclude 20 years after the program ended, that the positive effects of the Nuxalk Food and Nutrition Program are still evident.

-

- Kuhnlein et al., (2013).The Legacy of the Nuxalk Food and Nutrition Program for Food Security, Health and Well-being of Indigenous Peoples in British Columbia. BC Studies,179.

This article highlights the gaps of the Nuxalk Food and Nutrition Program in achieving food sovereignty. The authors argue that while improving the intake of nutritious food was successful according to several methods of evaluation, persistent food security exists due to the domination of industrial food products in diets, with local traditional foods play a supplemental role.

-

- Linda Tuhiwai Smith (2012).Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples. Zed Books Ltd, London. See also Tuck, E., 2013. Decolonizing Methodologies 15 years later. AlterNative: An International Journal of Indigenous Peoples 9, 365–372.

Understanding Indigenous food systems in the context of cross-cultural learning for food sovereignty requires a decolonizing methodology. Linda Tuhiwai Smith’s work challenges all learners to consider carefully how research and educational practices have been used in the past – and present – to either entrench or to contest and challenge oppression.

Questions:

- 1. Which methods for acknowledging and researching Indigenous food systems are most compatible with the principle of Indigenous Food Sovereignty and Social Learning?

- 2. What role could UBC Farm, the Centre for Sustainable Food Systems, and the Indian Residential School History and Dialogue Centre at UBC play in supporting the generation of knowledge and research that would support the conservation of local and regional Indigenous biodiversity and cultural heritage?

In British Columbia, wild salmon is a cultural keystone species of coastal Indigenous people's diets and cultures, playing a fundamental role in social systems including diet, materials, medicine, and spiritual practices of Indigenous people (Garibaldi & Turner, 2004). Due to their important role in transferring nutrients from marine to terrestrial ecosystems, salmon is also an ecological keystone species (Helfield & Naiman, 2006). Traditionally in British Columbia, wild salmon were harvested in large quantities and intensively managed for quality and abundance. Indigenous people saw a decline in the health and integrity of their cultures, ecosystems, social structures and knowledge systems as non-Indigenous fishers took increasing control of the fishing industry and as agriculture and other resource extraction activities affected salmon habitat.

Salmon has become an environmental and cultural policy issue in British Columbia. Decisions on fisheries in the province are driven by western science‐based knowledge systems and often exclude knowledge from non‐western based Indigenous sources (Fish-WIKS, 2017). Dawn Morrison promotes a regenerative and holistic health model as a path towards a sustainable food system. This model is a departure from the productionist model of the food system that was necessary for colonial expansion (see Indigenous Land and Food Chapter). The regenerative model does not use productionist language and Dawn Morrison suggests: “instead of calling yourself a producer, call yourself a farmer; and instead of calling food a product, call it its actual name,” (Morrison and Wittman, 2017). To improve fisheries governance and management, Canadian legislation needs to consider Indigenous knowledge as it can inform of a more sustainable system - environmentally and culturally.

Fisheries – Western and Indigenous Knowledge Systems (Fish-WIKS, 2017) is a research project out of Dalhousie University in Halifax, that looks at understanding how Indigenous knowledge systems can enhance decision-making with regards to the Canadian fisheries policy. Fish-WIKS propose that western governance bureaucratic theoretical model is at odds with the multiplicity of Indigenous knowledge systems.

The Wild Salmon Caravan is a community-based movement to that “celebrates the spirit of Wild Salmon through the arts and culture to help nurture the creative life-giving energy that wild salmon have inspired through the ages.” Check out the Voices of Wild Salmon page for powerful community voices talking about what wild salmon mean to them and why it is important to protect them and their habitat!

Readings:

- R. v. Sparrow [1990]. (2009). Retrieved from http://indigenousfoundations.arts.ubc.ca/sparrow_case/

This summary is of the 1990 Supreme Court decision which set out criteria to determine whether governmental infringement on Aboriginal rights was justifiable. The Sparrow Case was considered a victory as it affirmed Aboriginal rights, but no attention was paid to what was considered adequate consultation or compensation regarding rights infringement.

-

- Nesbitt, H. K. (2016). Species and population diversity in Pacific salmon fisheries underpin indigenous food security. Journal of Applied Ecology, 53, 1299–1633.

News release: https://www.britishecologicalsociety.org/press-release-hidden-salmon-diversity-sustains-first-nations-fisheries/

- Nesbitt, H. K. (2016). Species and population diversity in Pacific salmon fisheries underpin indigenous food security. Journal of Applied Ecology, 53, 1299–1633.

This article examines how species and population diversity – key measures of biodiversity - influence the food security of Indigenous fisheries for Pacific salmon. The findings show that population diversity, instead of species diversity, was associated with a higher catch stability. The authors suggest that the scale of environmental assessment needs to match the scale of the socio-ecological processes which will be affected by development.

-

- Kirchhoff, D., Gardner, H. L., Tsuji, L. J. (2013). The Canadian Environmental Assessment Act, 2012 and Associated Policy: Implications for Aboriginal Peoples. The International Indigenous Policy Journal, 4(3), 1-14.

The authors argue that Canada’s new Environmental Assessment Act (EAA 2012) weakens Indigenous peoples’ capacity to participate in the resource development review process for undertakings that affect their lands. In response to this insufficient EA process, the authors note that strategic environmental assessment could serve as a better alternative as it ensures that free, prior and informed consent is given.

Questions:

-

- 1. What do you believe is a meaningful policy change that could support Indigenous Food Sovereignty? At what level(s) can this occur – local, provincial, or federal? Who are the relevant Indigenous Peoples and who are the other stakeholders?

2. Any infringement of Aboriginal or treaty right in Canada requires justification. What are some different examples of infringement? How can the Canadian government create spaces of ‘meaningful’ and ‘ethical’ engagement with Indigenous Peoples

“There’s a lot of contention and also complementarity at the cross-cultural interface.” In her writing, Dawn Morrison reflects on the practice of intercultural engagement shown through local farmers and Indigenous people working together in the Peace Valley Region, together saying “no” to the Site C Dam development.

Dawn Morrison notes the generative potentiality of coming together across diverse knowledge systems and experiences in the Indigenous Land and Food chapter. According to Morrison, the ‘learning edge’ – or any edge – is where you’ll find diversity. In ecosystems, for example, the edge of a habitat is where the greatest species diversity exists. The learning edge, in the context of Indigenous food sovereignty, is where Indigenous peoples and their food-related knowledge, wisdom and values meet current federal, provincial or municipal policies that affect land, water and food systems. As Dawn suggests, there are gaps in knowledge in the framework for agricultural research and development, where Indigenous peoples were made invisible under the notion of terra nullius. Therefore, there are tensions at the edges where many farmers, fishers, hunters, and Indigenous peoples are coming together to realize the potential to work together to plan for the future.

Intercultural engagement between Indigenous people and settlers is challenged by the etymological underpinnings of the term ‘food sovereignty’. The term sovereignty is defined as ‘power or authority to reign over or control’ food. This is contradictory to an Indigenous worldview, in which food sovereignty is concerned with people working with the land, not controlling it. The challenges of cross-cultural assumptions and communication can, in turn, open the discussion to the real cultural differences between settler and Indigenous.

In The UBC Plan: Place and Promise, Aboriginal Engagement is one of UBC’s 9 commitments as it looks towards 2020. The goal, ‘Increase engagement and strengthen mutually supportive and productive relationships with Aboriginal communities’, aims to create spaces for intercultural learning. The Indian Residential School History and Dialogue Centre is one example of a physical space for these interactions to occur.

Readings:

-

- UBC. 2012. Place and Promise: The UBC Plan. Retrieved from http://strategicplan.ubc.ca/the-plan/intercultural-understanding/

This component of The UBC Plan outlines the goals and actions under each of the 9 commitments UBC has made looking towards 2020. While ‘portfolio action’ items are noted in The UBC Plan, they are high-level, which require faculty, staff and students to work collaboratively to comprehend and plant how they can contribute to a better UBC.

-

- Food Secure Canada. 2015. Resettling the Table: A People’s Food Policy in Canada. Retrieved from https://foodsecurecanada.org/people-food-policy

This document, compiled through kitchen table conversations, community meetings, and gatherings at the local, regional and national level by 3500 people across Canada, advocates for a national food policy that prioritizes the views of Indigenous people, people from rural and remote communities and in disadvantaged urban communities, and people working in the agricultural or fishing industries. Rather than looking at these groups as fragments, this policy considers the concept of food sovereignty for the whole.

Questions:

-

- 1. The university is often viewed as a champion for innovation and exploration, but lack of engagement with history coupled with a concern with political correctness can stunt open discussion of Indigenous relations in the classroom. For students who fear ‘vulnerability’ in the classroom, what tools can students or teaching staff utilize to overcome this?

2. Can any of the actions or ‘portfolio actions’ from The UBC Plan support intercultural engagement in your classroom?

3. What are some of the global challenges that we face today? How can the study of intercultural and international communication help us address global challenges?

-

- Barthel, S., Crumley, C., Svedin, U., 2013. Bio-cultural refugia—Safeguarding diversity of practices for food security and biodiversity. Global Environmental Change, 23 1142–1152. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2013.05.001

-

- Fish-WIKS, 2017. Exploring distinct indigenous knowledge systems

to inform fisheries governance and management on Canada's coasts. Halifax: Dalhousie University.

- Fish-WIKS, 2017. Exploring distinct indigenous knowledge systems

-

- Garibaldi & Turner. (2004) Cultural Keystone Species: Implications for Ecological Conservation and Restoration. Ecology and Society. 9(3):1 DOI 10.5751/ES-00669-090301

-

- Helfield & Naiman. (2006). Keystone Interactions: Salmon and Bear in Riparian Forests of Alaska. Ecosystems, 9(2), 167-180.

-

- Kirchhoff, D., Gardner, H. L., Tsuji, L. J. (2013). The Canadian Environmental Assessment Act, 2012 and Associated Policy: Implications for Aboriginal Peoples. The International Indigenous Policy Journal, 4(3).

-

- Kuhnlein et al., (2006). Documenting Traditional Food Systems of Indigenous People: International Case Studies. McGill University, Canada: Centre for Indigenous Peoples’ Nutrition and Environment.

-

- Kuhnlein et al., (2013). The Legacy of the Nuxalk Food and Nutrition Program for Food Security, Health and Well-being of Indigenous Peoples in British Columbia. BC Studies,179.

-

- Lao, A. Connecting Communities: Principles for Musqueum-UBC Collaboration. (N.d.). University of British Columbia, Canada: UBC Sustainability Scholars. Retrieved from https://sustain.ubc.ca/sites/sustain.ubc.ca/files/Sustainability%20Scholars/2015%20SS%20Projects/2015%20Executive%20Summaries/UBC-Musqueam%20Collaboration%20-%20UBC%20Sustainability%20Scholars%202015.pdf

-

- Martens, T., Cidro, J., Hart, M.A., & McLachlan, S. (2016). Understanding Indigenous Food Sovereignty through an Indigenous Research Paradigm. Journal of Indigenous Social Development, 5, 18–37.

-

- Morrison, D., 2011. Indigenous Food Sovereignty – A Model for Social Learning, in: Wittman, H., Desmarais, A.A., Wiebe, N. (Eds.), Food Sovereignty in Canada: Creating Just and Sustainable Food Systems. Fernwood Publishing, Halifax, 97–113.

-

- Morrison, D., & Wittman, H., 2017. Indigenous Land and Food, in: Peter Wall Institute for Advanced Studies (Ed.), Reflections of Canada: Illuminating Our Opportunities and Challenges at 150+ Years. Peter Wall Institute for Advanced Studies, UBC, Vancouver, 130–138.

-

- Reading, C.L. & Wien, F., 2009. Health Inequalities and Social Determinants of Aboriginal Peoples’ Health. Prince George, BC: National Collaborating Centre for Aboriginal Health.

-

- Linda Tuhiwai Smith, 2012. Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples.Zed Books Ltd, London.

-

- Tuck, E., 2013. Decolonizing Methodologies 15 years Later. AlterNative: An International Journal of Indigenous Peoples, 9(4), 365–372.

-

- Turner, N. J., et al., 2009. Chapter 2: The Nuxalk Food and Nutrition Program, coastal British Columbia, Canada: 1981-2006. In: Indigenous Peoples’ food systems: the many dimensions of culture, diversity and environment for nutrition and health. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

-

- UBC. (2017). Reconciliation Pole. Retrieved from http://ceremonies.ubc.ca/reconciliation-pole/?login

-

- Wittman, H. (2011). Food Sovereignty: A new rights framework for food and nature? Environ Soc Adv Res 2, 87–105. doi:10.3167/ares.2011.020106

-

- Working Group on Indigenous Food Sovereignty. (n.d.) Indigenous Food Systems Network. Retrieved from http://www.indigenousfoodsystems.org/.