Saturday Farmers’ Market Vendor Feature: Pure Pod Co.

This week we are featuring Pure Pod Co., a first-year vendor at our market! Pure Pod Co. uses organic and ethically sourced ingredients to create quality cacao-based beverages packed with powerful nutrients and antioxidants. We recently had the pleasure of chatting with the owner, Sarah Kerr, to find out more.

This week we are featuring Pure Pod Co., a first-year vendor at our market! Pure Pod Co. uses organic and ethically sourced ingredients to create quality cacao-based beverages packed with powerful nutrients and antioxidants. We recently had the pleasure of chatting with the owner, Sarah Kerr, to find out more.

How long has Pure Pod Co. been around? How did you get started?

Pure Pod Co. started this year. Our first market was on June 13th at UBC Farm. Last year, when I was in Costa Rica, I discovered a cacao pod. I cracked it open, tasted its sweet, sherbet-like flesh, and became fascinated with this tropical fruit, and all it had to offer. Chocolate was the only product I knew of that was made from cacao, but most chocolate is highly processed and full of sugar. I had no idea that raw, unprocessed cacao was a superfood – packed with antioxidants, nutrient-dense, and rich in theobromine (a natural stimulant).

What are the three most important things you think people should know about Pure Pod Co. ?

What are the three most important things you think people should know about Pure Pod Co. ?

- We use raw and natural ingredients that taste great, are nutritious and make you feel great.

- We care about people and the planet. Our ingredients are ethically- and sustainably-sourced, and vegan.

- We use biodegradable or reusable containers, to help you live a zero-waste, minimalist, and low impact lifestyle.

Many of our products are adaptogenic, what does apoptogenic to mean? What are the health benefits?

Many of our products are adaptogenic, what does apoptogenic to mean? What are the health benefits?

Adaptogens are plants (certain herbs, roots, fungi) that can support your body’s natural ability to cope with physical and emotional stress. They do this by working at a molecular level, regulating a stable balance in the hypothalamic, pituitary, and adrenal glands.

They are called adaptogens because of their unique ability to “adapt” their function according to the specific needs of your body. For example, if you are feeling anxious, they can help you feel more relaxed. If you are feeling down, they can help improve your mood.

Our Hot Cacao Adapotgen Blend contains the following organic adaptogens:

- Siberian Ginseng for reducing stress and inflammation.

- Astragalus for immune support

- Maca for energy, endurance and stamina

- Ashwagandha for mental alertness, vitality and a rejuvenated sense of wellbeing.

We use a tablespoon of this blend to make our Adapotgenic Cacao Smoothies too.

How do your source your cacao? What do you look for when finding a supplier?

West African countries, mostly Ghana and Cote d’Ivoire, supply more than 70% of the world’s cacao. As many as 2.1 million child labourers work in West Africa. When looking for suppliers of cacao, I wanted to be certain that no child labour was involved in the growing and production of cacao. The cacao we use at Pure Pod Co. comes from small-scale farms in Ecuador. The cacao is not only organic and of high quality, no child labour is involved and the growers are paid above fair wage. There is a focus on sustainable farming practices and we want to be involved in improving the quality of life for cacao growers and their families.

You use minimal and compostable packaging, why is this important to you as a company?How do you select the packaging for your products?

You use minimal and compostable packaging, why is this important to you as a company?How do you select the packaging for your products?

There is too much plastic in the world, clogging up our oceans and sealife.

We did not want our products to contribute to the waste problem.

We sell products that are healthy for the body, so the packaging needs to be healthy for the environment. For our take & make products, we landed on using a company in Ontario who has created OmniDegradable bags. These leave behind only water, CO2 and a small amount of organic biomass, all beneficial to plant growth, when they degrade.

At the markets, we serve Iced Tea and Cacao Smoothies in mason jars, which can be returned, recycled or repurposed. I hope that in the near future we can implement a mason jar refund system at the markets, so we can reuse the jars.

You have created many cacao based recipes, what goes into coming up with these?

Cacao is such a versatile ingredient, so it’s easy to be creative and incorporate it into a variety of recipes. I really enjoy cooking and experimenting with different ingredients and have fun in the kitchen. My son, who is two, helps with the taste-testing : )

My latest creations include Cacao Energy Balls using raw nibs, and Pumpkin Spice Hot Cacao, using raw cacao powder, spices, cacao butter, and oat milk. I post my cacao creations on our Instagram page, so feel free to check it out for some baking inspiration!

Why did you choose to come to the UBC Saturday Market specifically?

Why did you choose to come to the UBC Saturday Market specifically?

I love the atmosphere at UBC Farm. The Farm staff and volunteers are so helpful and the people who shop at the markets have time to chat, are friendly and genuinely interested in getting to know you and your business.

It’s also very family-friendly. My toddler loves to visit the chickens and wander around the apple orchard. You will often see him and my husband laid out on a picnic rug behind the Pure Pod Co. stall. I don’t know of any other markets in Vancouver that have the same vibe.

If you could only eat/drink one of your products for the rest of your life which one would it be?

If you could only eat/drink one of your products for the rest of your life which one would it be?

With the exception of Cacao Nibs and Cacao Butter, all of our products are beverages. If I could only drink one of my products for the rest of my life, it would have to be a tie between our Hot Cacao Adaptogen Blend, because you can make it into a hot drink, or use it to make a cacao smoothie and our Strawberry Cream Cacao Tea. It tastes as good as it smells, is caffeine-free and can be enjoyed at any time of day or night.

If I could only eat one of my products, it would be the raw cacao nibs. They have such a robust flavour, that is slightly bitter and nutty, and are so versatile.

Where else can customers find you?

You can also order from my website!

Market Dates|

Facebook Page |

Instagram |

Website

This week we are featuring Humblebee Meadery, a third-year vendor at our market! Humblebee Meadery has a hot take on the worlds’ oldest alcohol, bringing unique, refreshing flavours across BC. We recently had the pleasure of chatting with the owners, Jeff Gillham and Pierre Vacheresse, to find out more.

This week we are featuring Humblebee Meadery, a third-year vendor at our market! Humblebee Meadery has a hot take on the worlds’ oldest alcohol, bringing unique, refreshing flavours across BC. We recently had the pleasure of chatting with the owners, Jeff Gillham and Pierre Vacheresse, to find out more. How long has Humblebee Meadery been around? How did you get started?

How long has Humblebee Meadery been around? How did you get started?  For people who don’t know, what is mead? What is the process for making it?

For people who don’t know, what is mead? What is the process for making it?

Do you have dish pairing reccomendations for your different mead flavours?

Do you have dish pairing reccomendations for your different mead flavours?

Why did you choose to come to the UBC Saturday Market specifically?

Why did you choose to come to the UBC Saturday Market specifically?

This week we are featuring Pure Pod Co., a first-year vendor at our market! Pure Pod Co. uses organic and ethically sourced ingredients to create quality cacao-based beverages packed with powerful nutrients and antioxidants. We recently had the pleasure of chatting with the owner, Sarah Kerr, to find out more.

This week we are featuring Pure Pod Co., a first-year vendor at our market! Pure Pod Co. uses organic and ethically sourced ingredients to create quality cacao-based beverages packed with powerful nutrients and antioxidants. We recently had the pleasure of chatting with the owner, Sarah Kerr, to find out more. What are the three most important things you think people should know about Pure Pod Co. ?

What are the three most important things you think people should know about Pure Pod Co. ? Many of our products are adaptogenic, what does apoptogenic to mean? What are the health benefits?

Many of our products are adaptogenic, what does apoptogenic to mean? What are the health benefits?

You use minimal and compostable packaging, why is this important to you as a company?How do you select the packaging for your products?

You use minimal and compostable packaging, why is this important to you as a company?How do you select the packaging for your products?

Why did you choose to come to the UBC Saturday Market specifically?

Why did you choose to come to the UBC Saturday Market specifically? If you could only eat/drink one of your products for the rest of your life which one would it be?

If you could only eat/drink one of your products for the rest of your life which one would it be?

This week we are featuring Goodness Gracious, a first-year vendor at our market! Goodness Gracious is a small Vancouver Bakery specializing in delicious tarts, squares, and bakewells, using high-quality ingredients and home-style recipes. We recently had the pleasure of chatting with the owner, Grace Keenleyside, to find out more.

This week we are featuring Goodness Gracious, a first-year vendor at our market! Goodness Gracious is a small Vancouver Bakery specializing in delicious tarts, squares, and bakewells, using high-quality ingredients and home-style recipes. We recently had the pleasure of chatting with the owner, Grace Keenleyside, to find out more. What are the three most important things you think people should know about Goodness Gracious?

What are the three most important things you think people should know about Goodness Gracious? Bonnie’s Buttertart– I grew up in Eastern Ontario and butter tarts are quite a staple there. Mine are derived from an old family recipe and named of my granny. They are made with flaky butter pastry and a golden filling with a touch of maple syrup, these are very special treats. I offer “Just Butter” (plain), pecan, coconut, hazelnut, and raspberry crisp varieties.

Bonnie’s Buttertart– I grew up in Eastern Ontario and butter tarts are quite a staple there. Mine are derived from an old family recipe and named of my granny. They are made with flaky butter pastry and a golden filling with a touch of maple syrup, these are very special treats. I offer “Just Butter” (plain), pecan, coconut, hazelnut, and raspberry crisp varieties.  Blissful Bakewell– These traditional tarts are luscious British creations with almond frangipane and jam. We decided to swap traditional pastry for soft almond shortbread for even more richness and delight. Perfect with tea.

Blissful Bakewell– These traditional tarts are luscious British creations with almond frangipane and jam. We decided to swap traditional pastry for soft almond shortbread for even more richness and delight. Perfect with tea. Classy Caramel Square-These may look like your typical “Millionaire’s Shortbread”, but trust us – there is nothing typical about them. A melt-in-the-mouth shortbread base is covered in a thick layer of caramel, topped with chocolate. A classy combination of sweet decadence.

Classy Caramel Square-These may look like your typical “Millionaire’s Shortbread”, but trust us – there is nothing typical about them. A melt-in-the-mouth shortbread base is covered in a thick layer of caramel, topped with chocolate. A classy combination of sweet decadence.  If you could only have one of your baked goods for the rest of your life which one would it be?

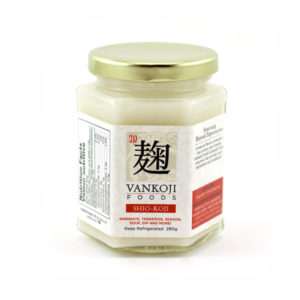

If you could only have one of your baked goods for the rest of your life which one would it be? This week we are featuring Van Koji Foods, a first-year vendor at our market! Van Koji Foods has rejuvenated an ancient Japanese ingredient, Shio-koji, to create a line of delicious sauces bursting with umami flavour. We recently had the pleasure of chatting with the owner, Tomani van den Driesen, to find out more.

This week we are featuring Van Koji Foods, a first-year vendor at our market! Van Koji Foods has rejuvenated an ancient Japanese ingredient, Shio-koji, to create a line of delicious sauces bursting with umami flavour. We recently had the pleasure of chatting with the owner, Tomani van den Driesen, to find out more.

Shio-koji (salt koji) is as neutral as salt and the ingredient is incredibly versatile. It is the

drive behind the business and our mission to introduce this to pantry’s of all cultures. It is the continued story from my country’s rediscovery of a lost product. This is our

premier product and continues to be our number one seller.

Shio-koji (salt koji) is as neutral as salt and the ingredient is incredibly versatile. It is the

drive behind the business and our mission to introduce this to pantry’s of all cultures. It is the continued story from my country’s rediscovery of a lost product. This is our

premier product and continues to be our number one seller. Shoyu-koji (soya – koji) uses the same process as Shio-koji, but utilizing soya sauce

(shoyu) instead of sea salt and water. This product was developed to provide the same taste and health benefits as Shio-koji, but replacing soya sauce in everyday Asian cooking.

Shoyu-koji (soya – koji) uses the same process as Shio-koji, but utilizing soya sauce

(shoyu) instead of sea salt and water. This product was developed to provide the same taste and health benefits as Shio-koji, but replacing soya sauce in everyday Asian cooking. BBQ-Sauce, this product was developed as something people can quickly relate to and enjoy. A mildly spicy Asian sauce that can be used on dishes that demand strong flavours. People are able to easily imagine using this on chicken, or in a stir fry. It is still a koji based seasoning, so it introduces people to the umami and that ….mmmmmmm…something extra that they will come back to talk about.

BBQ-Sauce, this product was developed as something people can quickly relate to and enjoy. A mildly spicy Asian sauce that can be used on dishes that demand strong flavours. People are able to easily imagine using this on chicken, or in a stir fry. It is still a koji based seasoning, so it introduces people to the umami and that ….mmmmmmm…something extra that they will come back to talk about. Garlic-Koji, this product is my my training wheels. This product is simply Garlic and Pepper mixed with Shio-koji and allowed to mature further. I developed it for similar reasons to the BBQ-sauce. Give people something they can relate to and imagine in their cooking.

This has proven to be my training wheels for people starting off with Shio-koji. It is hugely successful with first-time buyers as well as “seasoned” Shio-koji users. I now

have many customers that buy Shio-koji as well as Garlic koji at the same time. This pre-built Shio-koji mixture speeds up your cooking process by providing a base with

garlic and pepper already blended with Shio-koji. Use it straight or use it as the starter for something remarkable.

Garlic-Koji, this product is my my training wheels. This product is simply Garlic and Pepper mixed with Shio-koji and allowed to mature further. I developed it for similar reasons to the BBQ-sauce. Give people something they can relate to and imagine in their cooking.

This has proven to be my training wheels for people starting off with Shio-koji. It is hugely successful with first-time buyers as well as “seasoned” Shio-koji users. I now

have many customers that buy Shio-koji as well as Garlic koji at the same time. This pre-built Shio-koji mixture speeds up your cooking process by providing a base with

garlic and pepper already blended with Shio-koji. Use it straight or use it as the starter for something remarkable.

Why did you choose to come to the UBC Saturday Market specifically?

Why did you choose to come to the UBC Saturday Market specifically? Where else can customers find you?

Where else can customers find you?

This week we are featuring Vida Farm, a first-year vendor at our market! Vida Farm is a small scale urban farm focused on food security and community health, growing more nutritious, fresher and tastier vegetables with a lower carbon footprint. We recently had the pleasure of chatting with owner, Vida Rose, to find out more.

This week we are featuring Vida Farm, a first-year vendor at our market! Vida Farm is a small scale urban farm focused on food security and community health, growing more nutritious, fresher and tastier vegetables with a lower carbon footprint. We recently had the pleasure of chatting with owner, Vida Rose, to find out more. How long has Vida Farm been around? How did you get started?

How long has Vida Farm been around? How did you get started?  What are the three most important things you think people should know about Vida Farm?

What are the three most important things you think people should know about Vida Farm? Where is your farm located? What sets urban farming apart from farming in rural areas?

Where is your farm located? What sets urban farming apart from farming in rural areas?  If you could only eat one item from your farm for the rest of your life, which one would it be?

If you could only eat one item from your farm for the rest of your life, which one would it be? Where else can customers find you? And is there anything else you want them to know?

Where else can customers find you? And is there anything else you want them to know?